M. Zarifian

Peoples’ Friendship University

Russia, Moscow

е-mail: mohsen.zarifian@gmail.com

UNDERSTANDING THE WORLD BY MEANS OF CARTOONS IN MODERN MEDIA SPACE

Abstract. The topic of this study is inspired by my own personal skill in drawing cartoons, my professional experience as a cartoonist and journalist, and a profound long-term interest in exploring the communication capabilities of cartooning. In a nutshell, this article looks at how cartoons evolved as a Western branch of fine art from the stage of an artistic endeavor to achieve a deeper visual language to the deployment of cartoon capabilities with the goal of “public awareness” and as a means of visual protest during the Protestant Reformation in the early sixteenth century. From the Renaissance to the creation of the printing press, this evolution entered a new phase, focusing on the characteristics of political action. Stemming from the point that the main place and prosperous point of cartoons is in the press, the roles and functions of editorial cartoons have been analyzed. The objective is to come up with a suitable response to the topic of why cartoons are such excellent communication vehicles. This paper tries to explain how cartoonists, as excellent communicators, continually use written and visual means among the four basic modes of communication: verbal, nonverbal, written, and visual. Following that, it will be explained how cartoons will work very efficiently when you need to convey complicated and sensitive messages or need the participation of people. According to the findings of this study, cartoons are the outcome of human beings’ careful observation, which broadens our awareness of current human beings’ predicament in the new media landscape.

Keywords: cartoon, communication, caricature, journalism, editorial cartoon, political Cartoon, Mass Media.

Introduction

Cartoon as a Western branch of fine art dates back to the inventive examinations Leonardo da Vinci in the field of grotesque in order to find the ” ideal type of deformity”, which could be used to better comprehend the concept of ideal beauty [22, p. 16]. Regarding Cartoon terminology, the etymology is the Italian word “CARTONE” which means a finished preparatory sketch on a large piece of cardboard. The term Cartoon was used for preliminary designs, and the itself became the word for the drawing denoting “humorous drawing”. First known use in print media dates back to the mid 19th century, “cartoon” to refer to comic drawings was used in British Punch magazine[1] in 1843. Punch satirically attributed this term to refer to its political cartoons, and because of the popularity of the Punch cartoons led to the extensive use of the term [36, p. 261]. At first, caricatures and cartoons were merely an artistic attempt to reach a newer and deeper visual language and were not intended to raise public awareness. “Public viewing” and “public consciousness” appeared with the Protestant Reforms in Germany that swept through Europe in the early 16th century. During this religious reform movement, “visual propaganda” was widely used as a visual protest against the hegemony of religion. The context of religious reform was something widely familiar and well known to people from all walks of life, so these early cartoons were an outstanding tool for public awareness. The fact that the cartoon has been evolving as an art of visual protest since the beginning of the Protestant Reformation in 1517 to the present time should be an indication of its privileged position and role in the social movements. This capability of signifying meanings and susceptibility to interpretation is the legacy of satire that has really stood the test of time [35, p. 10].

Although they were born in Italy as part of the fine arts with a new visual language, cartoons found new life with the press in the form of editorial cartoon, which is also known as political cartoon or newspaper cartoon[2]. This evolution from the Renaissance to the invention of the printing industry by Gutenberg in 1455 entered its new phase toward the characteristics of political action. Cartoons have developed into a visual communication medium that engages the audience and helps them perceive and interpret the political, social, and economic scene in the locale, country, and around the world [38, p. 95-103]. On one level, focusing on cartoons without text and captions, this article attempts to study the concepts of cartoon perception by studying a series of research in the fields of semiotics and communication. In the following, given the importance of editorial cartoons in modern media, we have concentrated our efforts in this paper on editorial cartoons. Subsequently, the required skills for being a qualified cartoonist as an effective communicator have been reviewed. As a consequence, we have endeavored to find an appropriate answer to this major question: why are cartoons effective communication tools?

Literature Review

Because the art of cartooning is one of the culminations of visual and verbal communication, the field of cartoon studies is literally extensive. Researchers can follow different analyses through a succession of studies using a variety of paths. By investigating the distinctive characteristics of multi-modal discourse in cartoons, scholars of the cartoon genre have expressed their ideas on the manners in which they were used in cartoons and have related the features with the circumstances in which they were utilized.

Preliminary studies by Streicher [37] quoted in [3] and [29] collectively examine the communication performance of cartoons by emphasizing their exclusive characteristics. Considering this form as a means of communication, Medhurst and Desousa [26] pinpoint the rhetorical ability of editorial cartoons, and they carefully analyze the educational role of editorial cartoons in order to raise public awareness in the realm of fighting against AIDS and in South Africa. A number of researchers, such as Bivins [4] investigate the content of the form using Baldry and Thibault [2] based on Handl [21], to identify the key issues of representing citizens and parties.

Scholars have focused on the visual potential of cartoons to mirror political and social challenges in society in another set of studies. Morris investigates the power and dominance of cartoons in democratic growth, as well as the scope of their visual rhetoric [27; 28]. Likewise, Delporte [10], Feldman [18] and Edwards [12] scrutinize the artistic and linguistic style of cartoons in the fields of symbolic extents, satire, illustration, allegory, analogy, and narration; by means of case study analyses to underscore their assertions. Colin Seymour-Ure [34] evaluates the role and impact of cartoons in the changing British press landscape in tandem with the transformation of newspapers from printed format to digital version, with Olaniyan [30] exploring similar research towards print media in Africa. On visual eloquence, El Refaie [16] surveys the utilization of visual metaphors in cartoons, whereas Conners [7] analyzes cartoons in relation to pop-culture in an electoral background.

On the other extreme, scholars have paid close attention to how social representations are depicted in cartoons. Edwards and Ware [13] investigate how cartoons in the campaign media portray public opinion. Setting up identity in relation to people, groups, and nations by means of cartoons has been examined in the researches of Han [20] and Eko [14]. Moreover, Mazid [25] takes a look at the manifestation of ideological opinions in cartoons with Townsend, McDonald, and Esders [39] given their function within interpretation in political debates. In collaborating with Kathrin Hörschelmann [17], El Refaie [15] observes and studies the multi-literacy and interpretative capabilities of cartoons in various spheres in order to better analyze young people’s reactions to the political functions of cartoons. In light of this, Richardson, Parry [31] and Corner [32] put into the spotlight the competence of cartoons to visually destruct or advocate during electoral campaigns, along with their application in cataloguing unpredictable electoral phenomena. By reflecting upon earlier studies, Roberts [33] scrutinizes the communicative assignments and roles of cartoons in the context of elections.

- From understanding people to understanding the world

In any communicative process, the model of communication could be characterized as the following: communicator, communicative purpose; approach of the communicator to the communicative purpose and to the receiver; message body, which includes subject and topic; form of the message; message function and the recipient [41]. A communicator in a cartoon, including an editorial cartoon, according to this model, is the cartoonist or the author or editorial staff of the publication. As a result, the examination of the originality of an editorial cartoon as a specific type of creolized text reveals a key principle of individual authorship, from conception to execution. An editorial cartoon’s communication objective is to satirically critique a political event, behavior, or policy of a political figure. The communicator’s approach to the communicative purpose is almost always ironic and critical at the same time; the message is almost always dedicated to a current occurrence. Because the receiver’s immediate reaction and response is so vital in this sort of communication, editorial cartoons on long-past events are rather unusual [11].

Individual experience with the visual motif, as well as visual conformity and similarity, are used to create visual communications. While journalistic or academic texts are built on arguments and pleading for a cause, pictorial and graphical presentations follow logic with association; they connect diverse concepts that would not necessarily make sense in written or vocal communication. Because cartoonists can capture their audiences’ attention and offer them with a complete understanding of the subject in a single glance, the art of cartooning can be considered a rapid mode of communication. The peculiarity of a cartoon leads it to be used as an exceptionally versatile form of communication in order to exaggerate, magnify, overstate, and distort the traits of any personage or conspicuous features of a scenario in order to communicate the overall meaning, generating a resemblance of the original in order to convey the intended message.

A wide range of signs and symbols can be found in cartoons. A cartoonist’s expression is usually verbal, nonverbal, or both. This interpretation could be explicit or oblique. A “denotation” is the stated meaning, whereas a “connotation” is the implicit meaning. It blends semiotics and critical discourse analysis by examining the rhetorical function of irony in newspaper cartoons and how this metaphor is employed to generate ideology. It has been proposed that, in comparison to explicit communication strategies, deciphering metaphor-based communications needs greater cognitive work from audiences. As a result, the appreciation and remember of the text’s meaning may be enhanced. In any case, readers should first identify the opposing narratives before attempting to express the strategy of using irony to convey societal criticism. According to cartoon researchers, understanding the context surrounding the presented cartoon is critical in determining what the cartoon artist is attempting to say. The semi-logical resource becomes meaningless without this information.

According to a series of studies by Richard E. Mayer, professor of Psychology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and his team of researchers, cartoons are stronger and more impressive than at least 600 words [24, p. 64-73]. They drew the conclusion that cartoons are easier to remember and comprehend than text. Researchers declared that cartoons not only helped college students remember and grasp complex physics concepts better than the 600-word paragraphs presenting those concepts, according to researchers. Cartoons were more successful in most circumstances than cartoons containing 600-word sections. Cartoons communicate more effectively than text because they boost message understanding by 51% when compared to written communication. These findings lead to the deduction that cartoons are more memorable and understandable than text.

Other studies in the fields of data collecting, summarization, and organizing have yielded further intriguing outcomes. When information is provided to a recipient in a variety of formats, such as text, audio, video, or a mix of these, varied percentages of the concept are received and assimilated. Information in written messages is perceived at a volume of less than 10%. When audio data is included, the percentage rises to 40%, and when visual elements are included, it rises to 55%. Despite the lack of distinction between the relevance of verbal and symbolic signs at the level of speech and signs, M.A. Boyko [6] argues that information is interpreted by recipients in different ways.

Meanwhile, other researchers [38, p. 101] claim that cartoons help college students learn better and remember material longer than information presented in a word passage. Merely those who had seen the caricatures recalled 71% more than those who had only read the text. Exposure to cartoons may improve recollection and comprehension, as well as the ability to communicate the depicted situation clearly.

According to communication academics’ surveys on how audiences perceive newspaper cartoons, interpretation is entirely reliant on several various types of literacy, such as acquaintance with cartoon conventions, a comprehensive knowledge of current events, and the ability to make conclusions or comparisons. As a result, it is a challenge to all those who assume that cartoons are basic and easy to understand. The findings imply that even highly educated audiences that are somewhat more aware of political concerns need to master a wide variety of literacy abilities, such as analogies of idioms and metaphors, as well as other language skills, in order to completely understand the transmitted meanings in cartoons.

Understanding the world through editorial cartoons

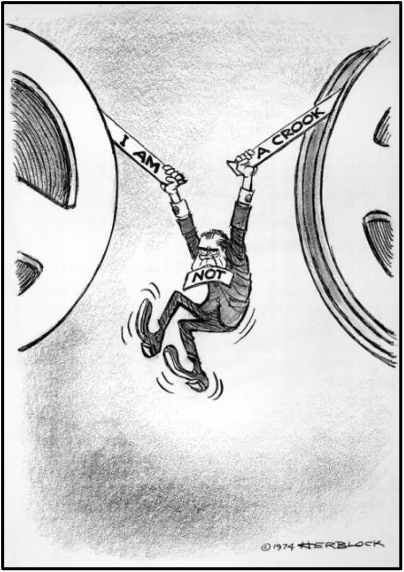

With the ability to distill news and opinions into a visual form, political cartoons present intelligent, power-packed, and self-contained commentary and analysis of current events. Packed with a numerous serving of creative satire, terse wit and a vivid imagination, without being directly critical, cartoons offer an open insight and interpretation on current affairs, in a very modest space. Political cartoons are a unique form of political journalism system and contrasts with frequent forms of communication. They should be considered as an anthology of journalistic acuity, which could be considered as a factor of building, forming and shaping public opinion [1, p. 265-267]; brevity and artistic singularity all serve in a fast and effective method of communication. At a time when politics is stuck in the interests of the majority, cartoonists criticize those in power without upsetting the readers. The cartoonists’ forte is characterized by sarcasm and frankness, and more often than not, position holders and the upper classes of society are his subjects of ridicule. They always work under restricted time conditions. The reason has settled in this fact that breaking news and leading events are continuously changing. Consequently, editorial cartoonists should be smart, fast, and dedicated as professional communicators to grasp the latest important topics. They are supposed to be fast and operative in order to react to events like social activists, draw cartoons, and publish them in appropriate periods of time (cart. 1). For this very reason, Political cartoons are being considered as a powerful communicative weapon [23].

[1] Punch or The London Charivari was a British weekly magazine of humor and satire established in 1841. Historically, it was most influential in the 1840s and 1850s, when it helped to coin the term “cartoon” in its modern sense as a humorous illustration. After the 1940s, when its circulation peaked, it went into a long decline, closing in 1992. It was revived in 1996, but closed again in 2002. (https://www.punch.co.uk/index)

[2] Hereinafter in this article “Editorial cartoon”, “Political cartoon” and “Newspaper cartoon” are applied with the same meaning, sense and purpose.

Cartoon 1. Nixon hanging between the tapes

Bohl mentions that editorial cartoons are essentially negative, critical, and cynical [5, 1997]. He states that the role of editorial cartoonist is to engender thought and inspire action amongst his audience. Accurate criticism of authorities should be his commitment. The editorial cartoonist must first and foremost have a political opinion to put across, and then have the courage to state the opinion [ibid]. Therefore, editorial cartoons are an instrument used to perpetuate the opinion of a person or group of people and influence others to gain that perspective. Unlike journalistic writing, they are not obliged to present facts and remain objective, although they operate in the same area and accomplish the same functions.

According to Feldman [19], satirizing political figures and events serves to attain two key objectives: One, editorial cartoons illustrate the core concerns surrounding circumstances, issues, or individuals and reflect the local political realities; two, they influence the political attitudes and tendency of the public towards the political process. Hereupon, they operate in a culture-specific atmosphere because, for the audience to discover the hidden meanings, they must be able to interpret correctly the various political issues and circumstances being parodied.

- Why cartoons are effective communication tools

It does not sound far-fetched that visual messages are one of the simple but most effective means of communication. Human beings are able to process pictures quickly, and that puts them far ahead of other forms of communication. It goes without saying that in a communication process, the recipient ignores a mountain of text, which gives detailed information, and prefers a transparent picture that you can assimilate in a fraction of a second. Cartoons and caricatures are usually much faster, cheaper, more flexible, and editable than videos or other visual productions. In the following, the communication capabilities of cartoons have been mentioned. It is discussed that audiences are hard-wired to comprehend symbolic imagery in cartoons and are eager to grasp the salient meanings of cartoons on board ahead of other forms of communication. All this means that, by understanding people and their demands, cartoons could become part of an extended, constantly changing communication effort. Based on the points below, it is possible to conclude that cartoons in modern media are extremely effective at communicating, which aids us in better understanding the world.

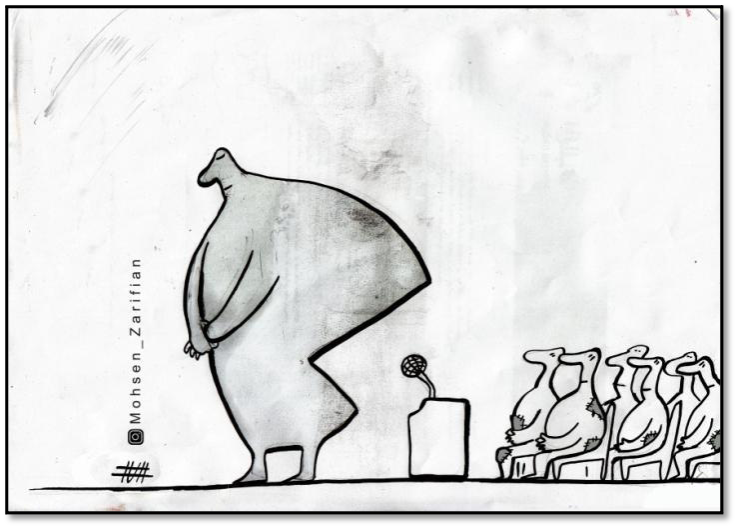

2.1. Cartoons make complicated and boring messages more understandable

Cartoons are an ideal medium to reach a really wide public. In most cases, cartoons are being used in public service communications, to illustrate their message, or to emphasize the written content of the message, just to ensure that those who are either illiterate or non-native speakers will grasp the main idea. The concept is conveyed in seconds without the need for a length full explanation. Reciprocally, when you have a message, you have to convey it with words; cartoons assist in emphasizing the message. Consequently, they are increasingly being used in scientific text books (cart. 2).

Cartoon 2. By Mohsen Zarifian

Illustrated communication is exciting, engaging, and works with many genres. You could use comic strips, cartoons, and other graphic storytelling approaches to inspire people to read, understand, and remember your messages [40, p. 20-23]. The high potency of the cartoon is its ability to convert confusing and complicated ideas into a simple, vivacious, obvious piece of communication. Cartoonists can take a dense strategic transformation journey, waggle their pens, and draw a magical “rich picture” out of it. In encountering a skilful illustration, audiences don’t scratch their heads as they attempt to grasp complex concepts. It has been predicted and drawn for instantaneous comprehension.

In a world where organizations communicate on an increasingly global scale, it’s an added value that cartoons can work just as well without words. Full-visual messages are scarcely lost in translation, making them extremely effective in communicating with audiences regardless of language barriers.

2.2. Cartoonists cut through the clutter

Cartoons follow this rule, which claims “A picture is worth a thousand words”. The effectuality and worthiness of cartoons in a communicative context is highlighted by artists whose simplicity in drawings summarizes complex events, articulating ideas that “encapsulate those metaphorical 1,000 words into a single picture” [9, p. 6]. Cartoons are often not talkative, but simple and effective. They sometimes speak sarcastically and sometimes directly to the audience, but go straight to the point. The cartoon’s simplicity and sharpness allow the message to be received and stored in the minds of the audience more quickly. Feldman [19] argues that while language is inarguably competent at conveying messages and putting arguments together, it does not have the proven ability of visual images to arouse emotions (cart. 3).

Cartoon 3. By Mohsen Zarifian

Moreover, to perform their professional duties, editorial cartoonists day by day follow the news in search of social and political issues and afterwards create visuals that sum up those thousand words into a single picture and criticize the policies and behavior of politicians when there is something inappropriate or incorrect with their leadership.

2.3. They bravely encourage people to participate

Communication scholars all agreed that, as it is with many subjects, visuals significantly assist in stimulating recipients’ interests. Cartoons have a big influence on the way different groups of people look at other parts of society. They can encourage audiences to look critically at themselves, and increase empathy for the sufferings and frustrations of others. They have a big responsibility to help people think more clearly about their work, and how they react to it. They can use their influence, not to reinforce stereotypes or inflame passions, but to promote peace and compromise. The crux of the matter is that cartoonists need to participate in social debate to encourage people to fulfill their social responsibilities (cart. 4).

Cartoon 4. Political cartoon by “Catalino cartoons”

Although the functionality of cartoons is not as an agent of change but as a statement of consensus, they invite members of society to remember cultural beliefs and values and participate in order to maintain them. As stated by Coupe [8], “like all journalists, the cartoonist is concerned with the creation and manipulation of public opinion” [ibid, p. 82].

2.4. Witty visuals make messages memorable

Cartoons, which are drawn without text and explanation, are considered a kind of fine art and also have the universality property like music. In encountering these types of cartoons, the viewer does not need to read captions to understand humor or underlying meanings. Cartoons could transcend language and time barriers. That is, knowing the language and linguistic complexity is not an obstacle for them; the viewer comprehends the meanings of the cartoonist by considering the signs and visual elements. This type of cartoon with susceptibility to interpretation is not about a specific time or particular event, and the message and idea behind them could be valid and applicable at any time and possibly anywhere; they assist in providing a clear mental picture, speeding understanding, helping memory, and providing a shared experience. Visual icons have been proven to strengthen concepts and make them more memorable. Potent and stylish visuals can help maintain engagement and encourage interaction long after the moment for which they were created has passed. They make great “take-home” messages and are full-fledged for sharing on modern mass media. The combination of metaphor, humor, irony, and allusion in cartoons is known for conveying prominent messages. Cartoons are principally appropriate for propagating ideas and messages in view of the fact that they easily draw the attention of audiences. It is generally believed that imagery leaves lasting impressions on the minds of viewers, for the reason that they last longer in the mind than words read or heard.

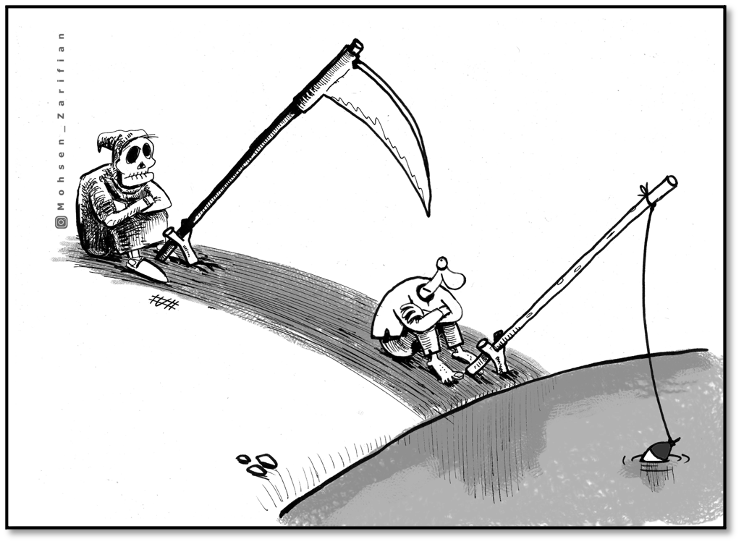

2.5. They make scary topics less threatening

Cartoons and humorous language in combination have the ability and power to turn disturbing, sensitive, and suspicious subjects into something controllable and manageable. The high potency of this combination is the ability to distill confusing and complicated ideas into a simple, comprehensive, obvious piece of communication. This is important when you want to communicate and convey a message that people find scary or unpleasant (cart. 5). Transmitting unpleasant messages in a formal format can create a defensive state in the recipient. But by using the element of humor in cartoons, communicators could be sure of receiving the full message. Humorous depiction of events and stories is the mainstay of editorial cartoons. But these messages are not often directly broadcast. They are hidden under a thick layer of innuendo, satire, and parody.

Cartoon 5. By Mohsen Zarifian

2.6. Cartoons arouse positivity, amuse, engage and inspire us

Funny pictures draw us in. It’s no secret that people like to be entertained, and this approach is perhaps all the more effective when they least expect it.

There’s a reason why audiences prefer boring textual presentations with cartoons. It provides an atmosphere, in which ice is broken, raises a laugh, and attracts people’s attention. The act of creating illustrations that document events in a presentation can break down communication barriers and establish a real emotional connection between the audience, communicator, and material. This offers organizations a powerful tool for communicating their visions and goals in a way that is compelling, inspiring, and engaging.

The precision, immediacy, and simplicity inherent in cartoons can be helpful in creating a feeling of positivity towards a concept. In terms of conveying the message, this might be especially helpful. Although imposing changes in communication methods could be frightening, at the same time, the innate charm, positive energy, and vivacity of the communicator could contribute to overcoming resistance and mediating negative thoughts and emotions. Cartoons also have childhood affiliations with humor, joyfulness, and entertainment, and during a dull or tense session, they could serve to relax listeners. They take the initiative as icebreakers, uniting the audiences with a sense of humor and the gratification of shared communication. This is particularly pleasant and exquisite when communicating with a group of people who don’t know each other.

Conclusion

From the discussions and findings in this article regarding the editorial cartoons, I may draw the following conclusion: Visual messages are literally condensed and concise and represent a clear summary of an event or issue at hand. As such, they are consequently given preference over traditional media news. It could be claimed that editorial cartoons assist viewers in reading the news and scanning through the meaning of an issue or an event, particularly for those audiences who give much preference to visual news and those who have limited time. The capabilities of cartoons to comment on social and political issues make them a distinct medium that contributes significantly by facilitating effective communication. Even if they may not be a means of socio-political participation, the way in which cartoons deconstruct social issues can have a vital impact on public perception of the modern human condition, or the state of contemporary society.

To recapitulate, it could be concluded that iconic signs are linguistic tools that are deep and valuable in their meanings, and they could offer easier interpretations and comprehension that are efficient and powerful, principally, when sensitive issues, such as political issues, are related and discussed. Additionally, the editorial cartoons are deployed to enhance fluent understanding and accurate perception of the messages on sensitive political subjects.

To bring this paper to a conclusion, I will summarize the main points as follows: Communication via cartoons is one of the most impactful means of communication in the era of contemporary media. In conclusion, the following are some of the findings: Cartoons make complex and monotonous ideas more fascinating and perfectly reasonable. People are encouraged to participate in social agendas by using cartoons. This study discovered that cartoons serve a useful purpose in converting complex and stressful meanings into simple and controllable concepts. This is critical if you are attempting to convey a message that people find frightening or uncomfortable. Cartoons stand out in a stream of text, photos, and videos. Cartoons and comics are typically far more rapid and flexible to create than videos or other more heavy-production graphics, which means they might become part of a broader, ever-changing communication process. In a presentation, using cartoons as a motivating medium will persuade the audience to embrace you as a communicator and lecturer. For a brief while during any session, there is a sense of convenience and thankfulness, and this transitory adjustment in attitude toward the message carrier could be leveraged to your advantage. The positive feelings elicited by cartoons used in presentations can sometimes be used to effectively support and help communicators. When a communicator has a difficult or sensitive topic to impart, it’s often preferable to to employ comedy to relieve the tension in the audience.

References

- Ashfaq A., Adnan bin Hussein “Political Cartoonists versus Readers: Role of political cartoonists in Building Public Opinion and Readers. Expectations towards Print Media Cartoons in Pakistan”. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 3 (MCSER Publishing), 2013, р. 265-267.

- Baldry A, P.J. Thibault Multimodal Transcription and Text Analysis: A Multimedia Toolkit and Course Book. London: Equinox, 2006, 301 p.

- Benoit W.L., Klyukovski A., McHale J., Airne D. “A Fantasy Theme Analysis of Political Cartoons on the Clinton-Lewinsky-Starr Affair”. Critical Studies in Media Communication 18, no. 4, 2001, p. 377-394.

- Bivins T.H. “Format Preferences in Editorial Cartooning”. Journalism Quarterly 36, 1984, p. 182-185.

- Bohl Al. Guide To Cartooning. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing, 1997.

- Boyko M.A. “Functional analysis of the means of creating the image of the country (on the basis of German political creed texts)” abstract of dissertation. Voronezh, 2006, 29 p.

- Conners J.L. “Popular Culture in Political Cartoons: Analysing cartoonist approaches”. Political Science and Politics 40, no. 2, 2007, p. 261-266.

- Coupe W.A. “Observation on a theory of political caricature”. Comparative Studies in Society and History 11, 1969, p. 79-95.

- Davies M. “Are We Witnessing the Dusk of a Cartooning Era?” Nieman Reports 58, no. 4, 2004, p. 6-8.

- Delporte C. “Images of French-French war: Caricature at a time of Dreyfus affair”. French Cultural Studies 6, no. 2, 1995, p. 221-248.

- Dugalich N.M. “Political cartoon as a genre of political discourse”. RUDN Journal of Language Studies, Semiotics and Semantics 9, no. 1, 2018, p. 158-172.

- Edwards J.L. Political Cartoons in the 1988 Presidential Campaign: Image, Metaphor, and Narrative. London: Routledge, 1997, 165 p.

- Edwards J.L, Ware L. “Representing the Public in Campaign Media”. American Behavioral Scientist 49, no. 3, 2005, p. 466-478.

- Eko L. “It’s a Political Jungle Out There”. International Communication Gazette 69, no. 3, 2007, p. 219-238.

- El Refaie E. “Multiliteracies: How Readers Interpret Political Cartoons”. Visual Communication 8, no. 2, 2009, p. 181-205.

- El Refaie E. “Understanding Visual Metaphor: The Example of Newspaper Cartoons”. Visual Communication 2, no. 1, 2003, p. 75-95.

- El Refaie E., Hörschelmann K. “Young People’s Readings of a Political Cartoon and the Concept of Multimodal Literacy”. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 31, no. 2, 2010, p. 195-207.

- Feldman O. “Political Reality and Editorial Cartoons In Japan: How the National Dailies Illustrate the Japanese Prime Minister”. Journalism Quarterly 72, 1995, p. 571-580.

- Feldman Ofer. Talking Politics in Japan Today. Brighton, United Kingdom: Sussex Academic Press, 2005, 224 p.

- Han J.S. “Empire of Comic Visions: Japanese Cartoon Journalism and its Pictorial Statements on Korea, 1876–1910”. Japanese Studies 26, no. 3, 2006, p. 283-302.

- Handl H. “Streotypication in Mass Media: The Case of Political Caricature in Australian Daily Newspapers”. Angewandte-sozialforschung 16, no. 1-2, 1990, p. 101-107.

- Hoffman W. Caricature from Leonardo to Picasso. New York: Crown Publishers, 1957, 150 p.

- Mateus S. “Political Cartoons as communicative weapons – the hypothesis of the “Double Standard Thesis” in three Portuguese cartoons”. Estudos em Comunicação no. 23, 2016, p. 195-221.

- Mayer R.E., Bove W., Bryman A., Mars R., Tapangco L. “When Less is More: Meaningful Learning From Visual and Verbal Summaries of Science Textbook Lessons”. Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol. 88, No. 1, 1996, p. 64-73.

- Mazid D.E. “Cowboy and Misanthrope: A Critical (Discourse) Analysis of Bush and Bin Laden Cartoons”. Discourse and Communication 2, no. 4, 2008, p. 443-457.

- Medhurst M.J, DeSousa M.A. “Political Cartoons as Rhetorical Forms: A Taxonomy of Graphic Discourse” Journal of Communication Monographs 48, no. 3, 1981, p. 197-236.

- Morris R. “Cartoons and the political system: Canada, Quebec, Wales, and England”. Canadian Journal of Communication 17, no. 2, 1992, p. 253-258.

- Morris R. “Metaphor and Symbolic Activity”. Visual Rhetoric in Political Cartoons: A Structuralist approach 8, no. 3, 1993, p. 195-210.

- Morrison M.C. “The Role of the Political Cartoonist in Image Making”. Communication Studies 20, no. 4, 1969, p. 252–260.

- Olaniyan T. “The Traditions of Cartooning In Nigeria”. Glendora Review: African Quarterly on the Arts 2, no. 2, 1997, p. 92-104.

- Parry K., Richardson K. “Political Imagery in the British General Election of 2010: The Curious Case of “Nick Clegg”. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 13, 2011, p. 474-489.

- Richardson K., Parry K., Corner J. The Palgrave Macmillan Political Culture and Media Genre: Beyond the News. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, 230 p.

- Roberts M. “Election Cartoons and Political Communication in Victorian England in Cultural and Social History”. Journal of the Social History Society 10, no. 3, 2015, p. 369-395.

- Seymour-Ure C. “What Future for the British Political Cartoon?” Journalism Studies 2, no. 3, 2001, p. 333-355.

- Shikes R.E. The Indignant Eye: The Artist as Social Critic in Prints and Drawings from the Fifteenth Century to Picasso. Boston: Beacon Press, 1969, 439 p.

- Spinozzi P. Origins as a Paradigm in the Sciences and in the Humanities. Göttingen: V&R unipress GmbH, 2010, 290 p.

- Streicher L. “David Low and the Sociology of Caricature”. Comparative Studies in Society and History 8, no. 1, 1965, p. 1-23.

- Suryawanshi A. “Communication through CARTOONS in times of Crisis”. Journal of Xi’an University of Architecture & Technology Volume XII, no. Issue II, 2020, p. 95-103.

- Townsend K.P., McDonald Esders L. “How political, satirical cartoons illustrated Australia’s workchoice debate”. Australian Review of Public Affairs 9, no. 1, 2008, p. 1-26.

- Wylie A. “Communicate with comics: Moving people to act with illustrated storytelling”. Public Relations Tactics, July 2012, p. 20-23.

- Yakobson R.O. Language and the unconscious. Moscow: Gnosis, 1996, 234 p.